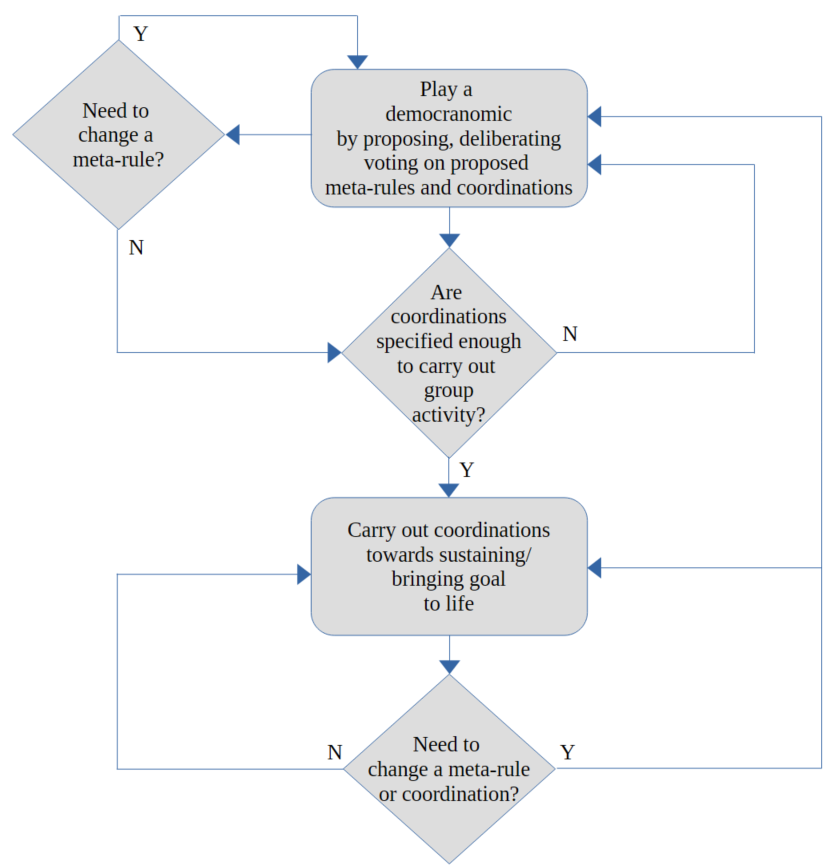

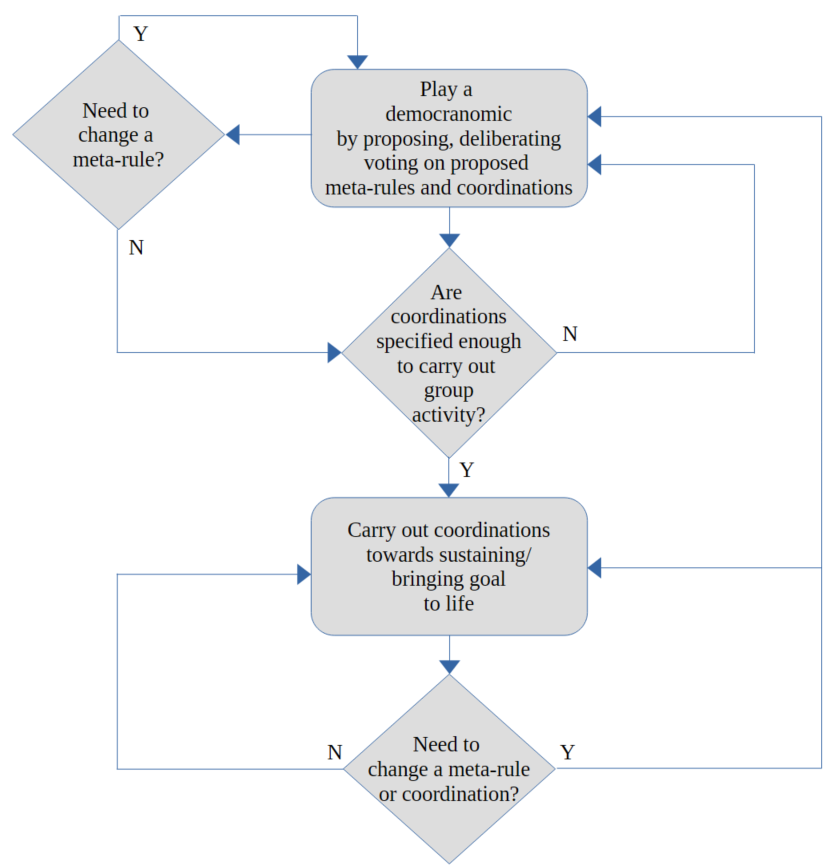

Decision Flowchart for making Meta-Rules and Coordinations

Democranomic is a serious tabletop game. Not so serious that laughing is forbidden. Rather, it’s a game played towards a serious goal. The goal is for players to make a group-chosen, real-world project or organization. They could make something small like a one-time board game party or film screening, or a reoccurring discussion group or lunch club. Or they could choose to create something bigger like a street theater troupe, a group trip, a service club or a community festival. The ambitious could choose to make a cooperative business like a restaurant, housing coop or charter school.1 Playing a democranomic is a way for people to democratically identify and develop a common interest. These are “serious” goals because, unlike other tabletop games which largely exist in players’ imagination, a successful democranomic uses players' imagination to specifically and intentionally organize part of the real-world.

The name “Democranomic” is a combination of the words “democracy” and “nomic”. Democranomic is a type of nomic, one used to democratically forge a real-world project. What is a nomic? A philosopher named Peter Suber invented a game called Nomic where it is a move to change a rule of the game. It is a game of self-amendment in which all players can redefine the rules of play.2 In Suber’s original rule set3, each player’s turn has two parts: First, the player can propose a rule-change. Second, the player rolls a die and collects its points towards the goal of being the first to reach 100 points. About this goal, Suber said, “this rule is deliberately boring so that players will quickly amend it to please themselves”.4 His initial rule set also requires that proposed rule changes pass a vote of the players to be adopted. In this way, the goal can be changed (it’s just a rule after all), but only to something the players support. Like a nomic, a democranomic uses its rules to describe how to make other rules. But a democranomic goes further and also use its rules to specify coordinating actions that the group carries out in their attempt to realize their chosen goal into existence.

Describing Nomic as a “game” makes it an easy way of both understanding and actually building a small-scale participatory democracy. Compare a nomic with the common understanding of a generic tabletop game. Generally, in such games players gather together and take turns doing structured actions towards some game-defined goal5 in a shared imaginary context, all within fixed sacrosanct rules. Nomics have a similarity and a difference to this definition. Similarly, a nomic starts by using a turn mechanism, which democratically gives all players a nearly equal chance to take an action to influence the shared context. Differently, although some tabletop games allow limited game-controlled modification of some rules (like Fluxx, Red7 and Anomicrazy), a nomic allows the full player-controlled modification of all rules.6 Ideally, players of a democranomic will use rule-making to coalesce around making their goal real. Through the game’s rules, they try to co-author a “knowledge of how to combine”7. The idea of democratically unifying is simplified when it’s seen as just playing a turn-based game of proposing and voting on self-coordinating rules.

One could sincerely ask, “Won’t proposing, discussing and voting on every rule slow things down a lot?” Certainly. Especially when compared to playing a regular pre-built tabletop game. But in a democranomic, players are building the game while they are playing it. Democranomics won’t move fast and will be spread over many sessions, possibly running the length of the project that’s built. Hopefully once the players build many of their meta-rules (rules about making rules) things will move faster. Meta-rules could also include ways that try to move things along, such as letting anyone call a vote at anytime to end discussion over a proposed rule and begin voting on the rule (cloture). Another way to speed things up is to start playing a democranomic with a pre-built initial meta-rule set8 (possibly even with a predefined goal), rather than building one from scratch. Once the meta-rules get somewhat established (and they can always be changed), they are then used to discover and set a goal (if not preset) and build another set of rules called coordinations that define the actual operations of the group’s real-world project.9 As in any participatory democracy, doing this constructively requires trust-based good-faith10 time-consuming possibly-frustrating deliberation and compromise. Potential players should know that part of a nomic is discussing proposed rules and interpreting how rules apply when unforeseen situations happen. So people in a rush for action and allergic to "analysis-paralysis"11 will not enjoy playing a nomic. As with anything, there is a balance to be found here, between consideration and progress.12

Of course not every coordination can be specifically spelled-out in the rules. Doing so is unnecessary and overly cumbersome. For instance, a board game group does not need to create rules about what people should wear to their get-togethers. It is often better to rely on the group’s ability to informally work many things out, and only build rules for situations where this does not naturally happen, or where it’s important for things to happen in a certain way. For example, a group may wish to allow a deliberation to happen casually like a conversation, but they make a rule that anyone at any time can invoke a predefined “structured deliberation” because, in the past, the group realized that sometimes certain people dominate the informal deliberation. As another example, to ensure a consistent product, a restaurant co-op might make a rule defining a specific cinnamon bun recipe. Likewise, rules very distant to core operations may be unnecessary. It makes sense that a food-serving group wants to ensure cleanliness and so puts sanitation procedures into their rules, but a discussion group probably does not need such rules (unless viruses are a concern). Groups having difficulty agreeing on the appropriate uses of rules may need time to reach a shared understanding, or may collectively hold too wide a range of opinions to constructively collaborate.

When a democranomic starts, players should understand that it is an experiment, and one that very well may fail, especially due to losing participants. Players are always free to stop playing, especially as the time and effort commitments become more clear, or if the goal starts heading in a direction they do not find interesting. Players may also attempt to split the group if multiple popular but incompatible goals emerge. In fact, splitting the group to following different goals could be a good thing, since it creates additional democranomics with players pursuing more-satisfying goals.13 Since Democranomic is meant to be a cooperative and humane game, rules against leaving or splitting the group should never be made (or respected if made). The group only stays together voluntarily, based on shared interest and trust, not on coercion. A democranomic’s rules are meant to organize not force, with an exception of graduated sanctions14 for those who do not play by the group's rules. It's possible a player will choose to disrespect and disregard a rule. What if a rule says “Only the person holding the tennis ball may speak”, and Bob willingly and repeatedly chooses to interrupt the tennis ball holder even after many reminders of this rule? In such cases, where a player clearly and continually ignores rules, the group is justified in temporarily or permanently removing the player in a democratic group-built way. A democranomic’s success depends both on the players finding ways to work together, and on the reciprocal trust between the players and the group.15

(Starting with the rules: 1. Each player takes turns proposing one rule change, such as an addition, alteration or removal of a rule. 2. All rule proposals are immediately voted on with a show of hands. Those getting 50% or more are passed).

● Person A proposes that all votes are done by secret ballot (fails vote).

● Person B proposes changing the vote passing threshold to 60% (but the vote on this doesn’t get 50%, so it doesn’t pass).

● Person C proposes the group purpose is to regularly discuss and enact democracy (passes with > 50% of vote).

● Person D proposes that the group’s meetings will begin with a short (< 10 minutes) reading about democracy, chosen by a random person set in the previous meeting (passes with > 50% of vote).

● Person E proposes that people in the very first meeting can unilaterally block (veto) any rule made by people who first appear in a later meeting (fails vote).

● Person F proposes that the rule-making part of each meeting will stop after two rounds in which everyone gets a turn (passes).

● Person G proposes that everyone has to wear purple to each meeting (fails vote, but just barely).

● Person H proposes that each proposed rules change should be sent to all group members at least 3 days before the next meeting so they may consider the rule before voting. This passes. (Discussion ensues about if this rule should come into effect now, and what that would entail, or comes into effect next meeting).

And so on… Note that both meta-rules (persons A, B, E, F, H) and coordination rules (persons C, D, G) are being developed simultaneously. As democranomics progress, meta-rules will probably become more stabilized and used to make coordination rules, which eventually will also likely become stabilized as well. But, being a democranomic, both should remain changable at anytime the group feels change is needed.

I) People are chosen for the online administrator role(s) and the in-person meeting facilitator role(s).

II) The group will have an in-person rules meeting every 2 months, started on the 1st of each odd-numbered month. The meeting markes the beginning of a cycle.

III) A rule is designated by a roman numeral (i.e. I, II, III, ...).

IV) Rules can be discussed during both the in-person meetings as well as an on-going email discussion, but they can only be proposed and voted on in the email discussion. General discussion emails should be sent to [gen_email_address], while proposals and votes should be send to [util_email_address]. Email was intentionally chosen for it's slowness (to encourage people to take their time thinking about what they want to say). During the email discussion, members can make any number of general discussion messages. A member can also make a limited number of proposals to (a) add or remove rules, or (b) ammend existing rules. They can also cast votes on any of these proposals. Proposals and votes are anonymous. General messages are not. We are creating a software tool that will allow us to impose automatically-checked limits on the number of proposals and votes and anonymous a member can make, and to allow them to do so anonymously. The tool requires each member to randomly retrieve one sheet of paper from a bag at the in-person meeting. Each paper will have several randomly generated alpha-numeric codes. The member will "spend" one code on each anonymous proposal or vote that they email. Members should have an identifiable email address, that they register with the administrator, for non-anonymous general messages. For anonymous proposals or votes, members can use any email address, and put one of their codes in it. We will have a website at [website_location] that will be updated once a day that will show the proposals and votes. This website and the proposals will be cleared at the end of each cycle. Those proposals that get votes greater than or equal to 3/4th's of the total number of members will be incorporated into the group's rules.

V) When creating a proposal or vote email, place one of your alpha-numberic codes in the subject line with nothing else. Then, in separate lines in the email's body, do the following

A) For adding/removing a rule:

1) Add: or Remove: followed by either the text of the rule to be added, or the number of the rule to be removed.

B) For ammending a rule:

1) Ammend: followed by the rule number

2) Line: followed by the line number where the change starts

3) Text: followed by the text of the change. Your email application must be able to support formatting, because in your changed text, any removed text must be striked out and any added text must be italicized. Moved text should be removed from one place and added to another.

C) For voting on an addition/removal/ammendment:

1) Vote: followed by the proposal number

VI) Limits on proposals and voting. Each cycle:

A) A member can make up to 3 proposals.

B) A member can cast one vote on each proposal. They cannot vote on their own proposal

VII) Rule meeting

A) Meetings last an hour and a half

B) The meeting's agenda is open, however it's assumed that people will be talking mostly about the past cycle's proposals.

C) People should roughly sit in a circle or square (in some way where it’s obvious who is next in order), in case a “structured discussion” is called.

D) The meeting can be informal unless any one person says “Structured discussion”, and someone else says “Seconded” at which point an immediate vote of hands is taken. Should > 50% (rounded up) of people put their hand up, then the structured discussions starts: People should already be roughly sitting in a circle or square (in some way where it’s obvious who is next in order). Starting with the facilitator and going clockwise (as if looking down from above the room), each person maybe speak for at most 20 seconds (timed by the facilitator, who gives a 5 second warning and end warning). People don’t have to use all 20 seconds and can pass rather than speak. At the end of each round, a hand vote is done to see if another round of discussion should happen. Each time another round happens, the speaking lengths are shortened by 3 second, but shortens no further than 11 seconds speaking lengths.

VIII) Meeting locations/times (for rules-meetings) and location/days/times (for non-rules-meetings) will be set with doodle.com. The online administrator will start the next rules-meeting location doodle poll within a week after the last rules-meeting. Pools for non-rules-meetings can start whenever the group decides to have such a meeting.

(Used with the above meta-rule set).

I) GOAL: To build in-person community around having respectful, enlightening and science-supported discussions around ecological topics.

II) Each group will have at least on discussion meeting every two months. As with the meta-rules, meeting times and places will be scheduled with a doodle.com poll set up by an administrator.

A) These meetings will be used for the following activities: First and foremost, we are interested in talking about the ecological topics and ideas (like a book club). With enough interest, we might collectively do fun activities (like a social club) and meaningful activities (like a service club) that align with ecological topics. Example activities:

1) Discussion activities might include informal discussion, topical talks by members or guests, presentations, interactive show-and-tells or talk centered around shared video clips or web pages. A discussion meeting be entirely an informal whole-group discussion, or it could be a scheduled of one long presentation or several shorter presentations (all followed by discussion).

2) Social activities might include walks, hikes, bike rides, shared ecologically-friendly meals, visiting natural history museums.

3) Service activities might include stream cleanups, starting community gardens, doing letter-writing campaigns on ecological issues.

III) After the discussion part of a meeting concludes, there will be a short organizing session to see if anyone wants to present something topic-appropriate at a future meeting, and if there’s interest in the group doing any other type of activity beside discussion. If there is any interest for either, or just for the next discussion, a rough scheduling will be attempted, which will be finalized with an administrator holding a doodle.com poll online.

Note: This coordination rule set is still very informal. If the group finds out it needs more specifics (for instance, to build a formal list of appropriate discussion topics, or to make a procedure for scheduling presenters for each meeting), then it would use the meta-rules to build additional coordination rules for these needs.

1. If attempting a cooperative business, it should probably not be a capitally-intensive type, since dispersed ownership tends to complicate capital formation.

2. Note that the passing of rules is very different than the implementation of rules. For example, if the group depends on some third-party online service to communicate, and then passes rules specifying changes to how that service works, it may be difficult or impossible to actually change the service (especially one they don’t own or control) to work as their new rule describes.

3. See https://legacy.earlham.edu/~peters/writing/nomic.htm

4. Suber, Peter (2003). "Nomic: A Game of Self-Amendment". Earlham College. Archived from the original on 2020-03-03. Retrieved 2023-12-15.

5. A nomic can be constructed so that players work either competitively (like Risk or Chess) or cooperatively (like Pandemic or Forbidden Island) towards a goal. A democranomic is both competitive and cooperative as players attempt to constructively collaborate while possibly advocating different visions and paths forward.

6. Full freedom to change rules also means this same process can be used to destroy a nomic’s democratic structure. Also, since a game’s goal is defined in it’s rule set, being able to change any rule means being able to change the goal.

7. In his book Democracy in America, the 19th-century French student of American democracy, Alex de Tocqueville, saw all sorts of people organizing around various topics and scales: "Americans of all ages, all stations of life, and all types of disposition are forever forming associations. There are not only commercial and industrial associations in which all take part, but others of a thousand different types - religious, moral, serious, futile, very general and very limited, very large and very minute." Crucially, he stressed the importance of the skills learned in group work. He said, "In democratic countries knowledge of how to combine is the mother of all other forms of knowledge; on its progress depends that of all the others". He believed associations reduced isolation and individualism, and was a way people discovered and pursued common interests in a democracy.

8. For instance, see Martha’s rules and here, or Rusty’s rules (which might be over-specified) or Robert’s rules (which are a slog). In addition to starting with pre-made meta-rules, a democranomic could also start with pre-made coordination rules. Would such a situation still be considered a democranomic, if it was not built in a directly-democratic way? Perhaps so if the meta-rules and coordinations still used directly-democratic ways to allow for further self-ammendments.

9. The word “rule” implies “you must (not) do this” while the word “coodination” implies “this is the/a way we have chosen to do this”, where the first conveys dominance and second cooperation. “Rule” is conventionally used here since that is the term used by tabletop board games. But a “coordination” is a type of modifiable agreed-upon rule where clarity is the goal rather than coercion.

10. There will always be differences in opinion and style during deliberation. This is a normal and productive part of a deliberation, and can create constructive opportunities when done in good faith. However, when done in bad faith, it can be part of an effort to covertly sabotage the deliberation. There can be those who try to intentional delay, distract, derail, confuse and dispirit other deliberators. Such people attempt "'vandalism of the discourse' and 'intellectual terrorism' where the goal is not to promote one specific idea but to destroy the discourse as a whole". Ideally, the group initially gives members the benefit of the doubt, and uses evidenced observed over repeated interaction to judge a member's intention, while holding in mind that honest people frequently disagree.

11. Google Gemini defines this as “a state of indecision caused by overthinking a problem or situation, leading to an inability to make a choice or take action. It occurs when an individual or group is overwhelmed by too much information or too many options, often driven by a fear of making the wrong decision or a desire for a perfect solution.” This is often the very work of deliberation, and part of the process of selecting the best way forward.

12. The slow turn-mechanism may fall away as the meta-rules and coordinations somewhat stabilize since, at that point, much of the activity will center around carrying out coordinations and can likely be delegated and happen simultaneously (outside of turns). But turns may still be useful if/when meta-rules and coordinations need updating.

13. With or without a split, players can try to recruit outsiders into ongoing games to (re)build its size. Players might attempt to participate in multiple democranomics at the same time, but doing so will be difficult since each one likely needs a large time commitment.

14. Elinor Ostrom argued that effective commons management requires graduated sanctions, an escalating system of punishments for rule-breakers, rather than harsh immediate penalties, to avoid resentment and encourage continued cooperation. She identified this as a key design principle for robust self-governing systems, starting with low-impact penalties that serve as reminders, allowing for rehabilitation and trust rebuilding, and only escalating for repeated or severe offenses. (from Gemini)

15. There is often value from differing viewpoints when that difference can be expressed civilly and engage constructively. This is often challenging for those who build themselves narcissistic identities on being the gleeful contrarian, the rebel, the irreverent rulebreaker, the challenger, the know-it-all, the jokester. A democranomic does not need attention-seeking personalities. It needs communicators able to place attention on ideas and their merits in considerate well-intentioned ways.